Professor VonBlume is objectively, one of my best drawings; prints sell well, people point it out single it out from my booth at cons, and it makes better use of lighting than anything else I’ve done.

It took everything I had to get it to the point where I no longer hated this piece, doubted my own artistic ability, or curled into the fetal position when thinking about it.

Concept

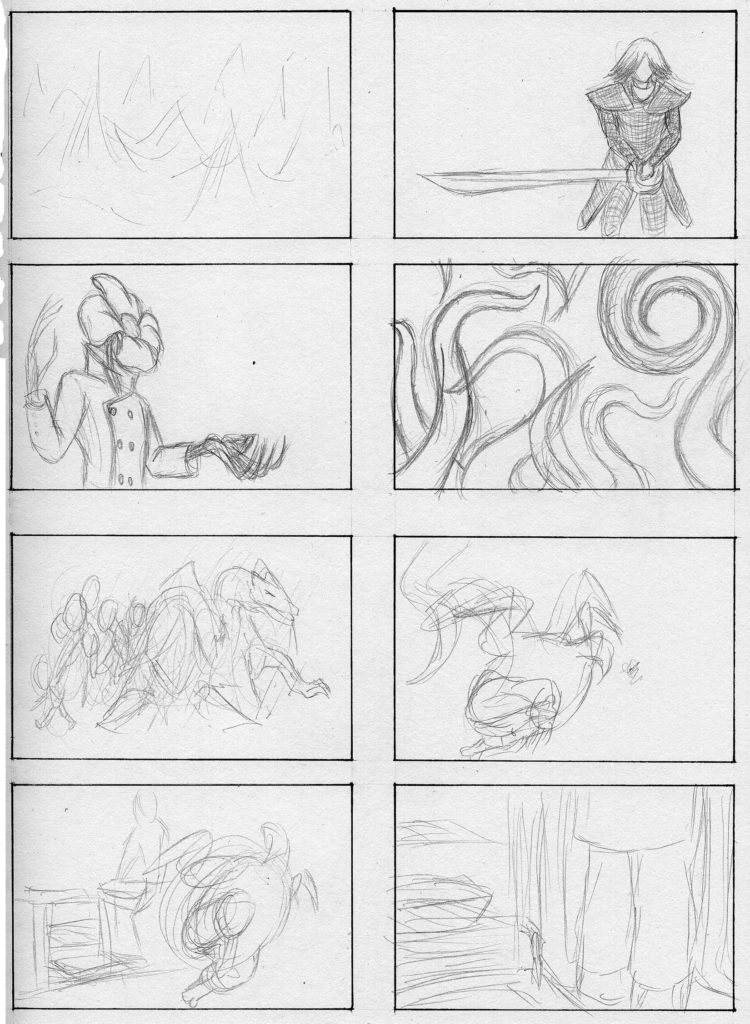

At first it was just a concept sketch. Just one little thumbnail amongst a page of other random things that popped into my brain that day.

The last three thumbnails on this page revolve around an oven-ready turkey making its escape from an oven.

I think we’re all glad that I, instead, took my inspiration from the second row.

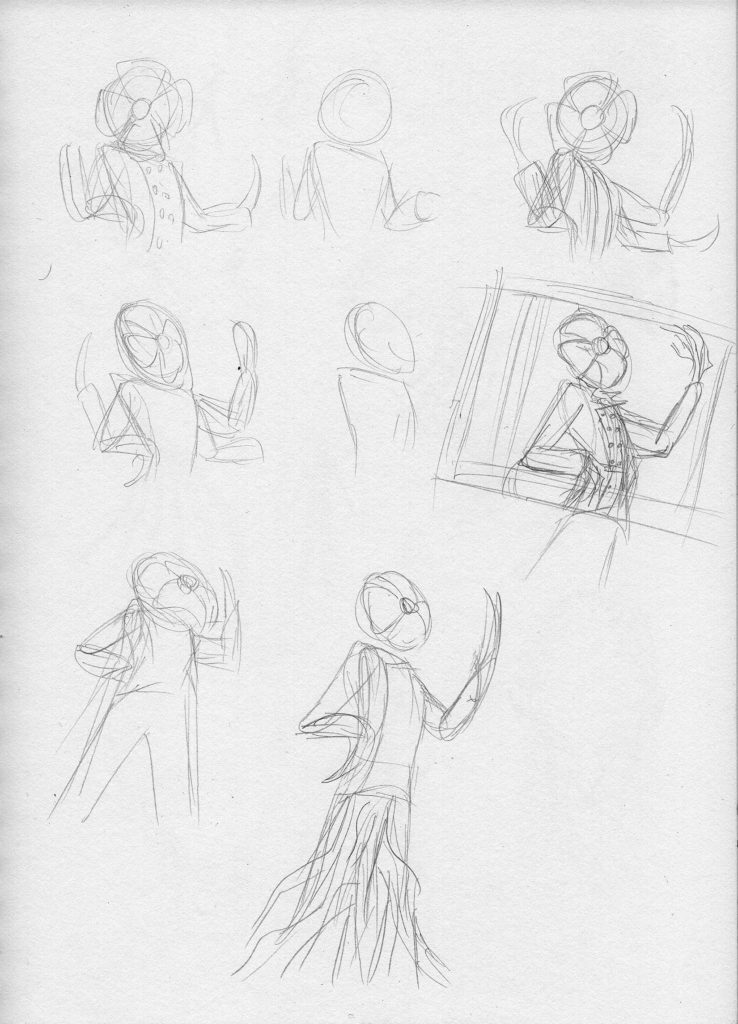

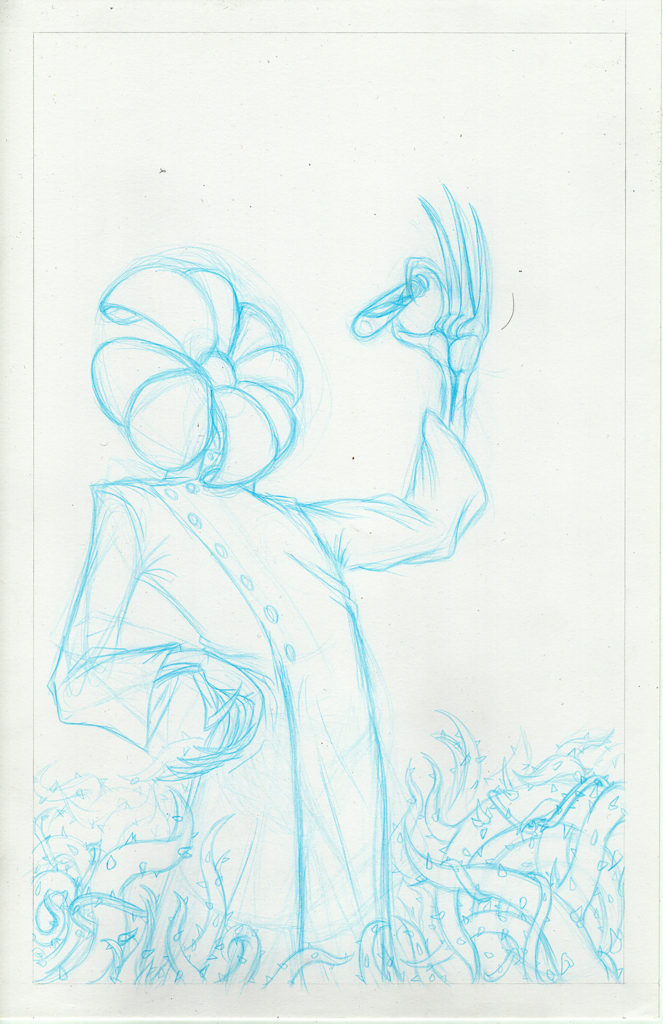

With said inspiration in-hand, I did more rough sketches; placing the Professor in various poses and trying to find an interesting composition for the drawing.

Things were going well.

I figured out who the Professor was: a mad scientist that, somehow, turned himself into a plantman.

I figured out what the Professor was doing: revelling in his new discovery amongst his viney minions.

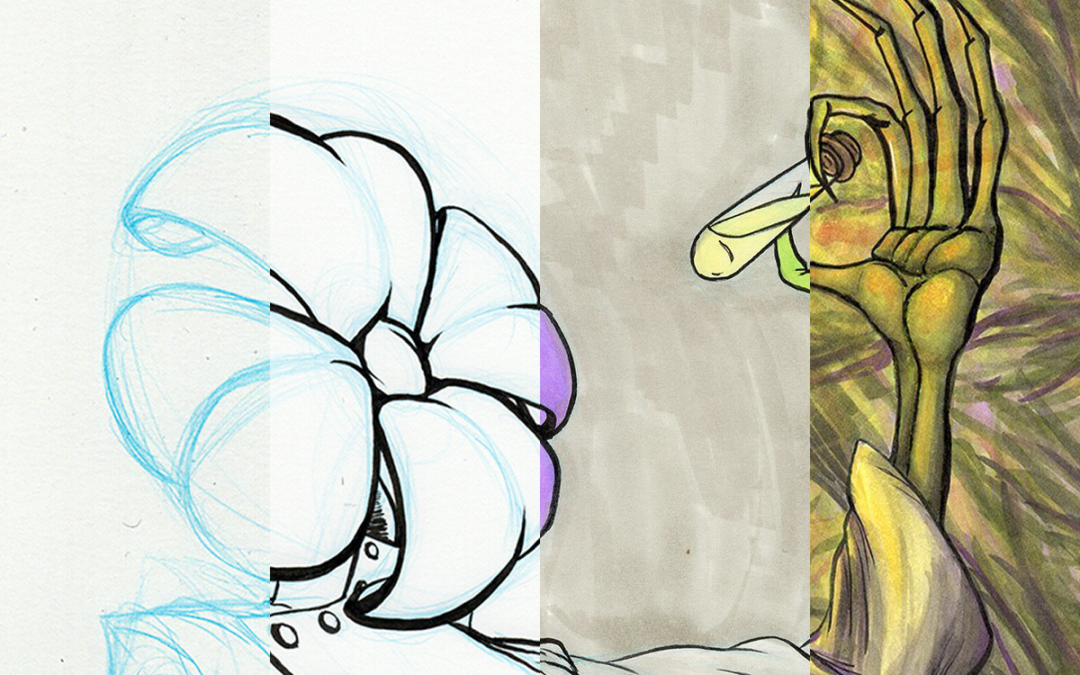

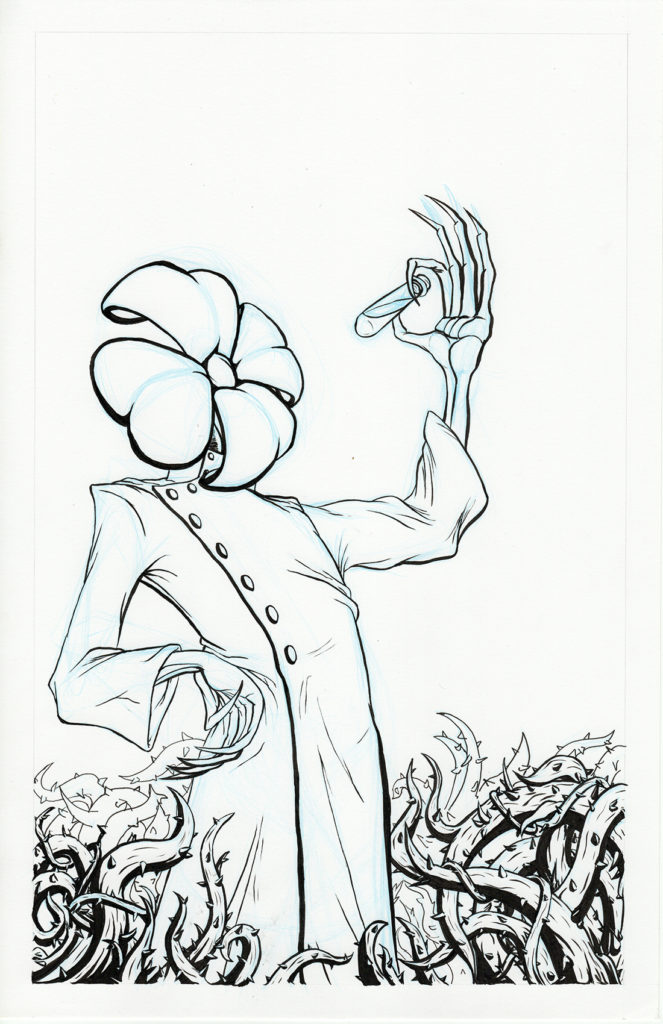

Drawing

I had a pose and composition I liked and the initial pencil drawing was looking promising.

Inks followed. Things were looking even better.

Then the doubt set it.

Panic

When it comes to art, no other aspect terrifies me as much as colour.

I’ve studied colour theory several times.

I understand which colours work together; I understand which don’t. I understand what pigments are. I understand the physics of how they work and how they work together. I understand colour on every level possible.

What I don’t understand, is why my understanding of colour is so completely useless when I try to apply it to the actual piece I’m working on.

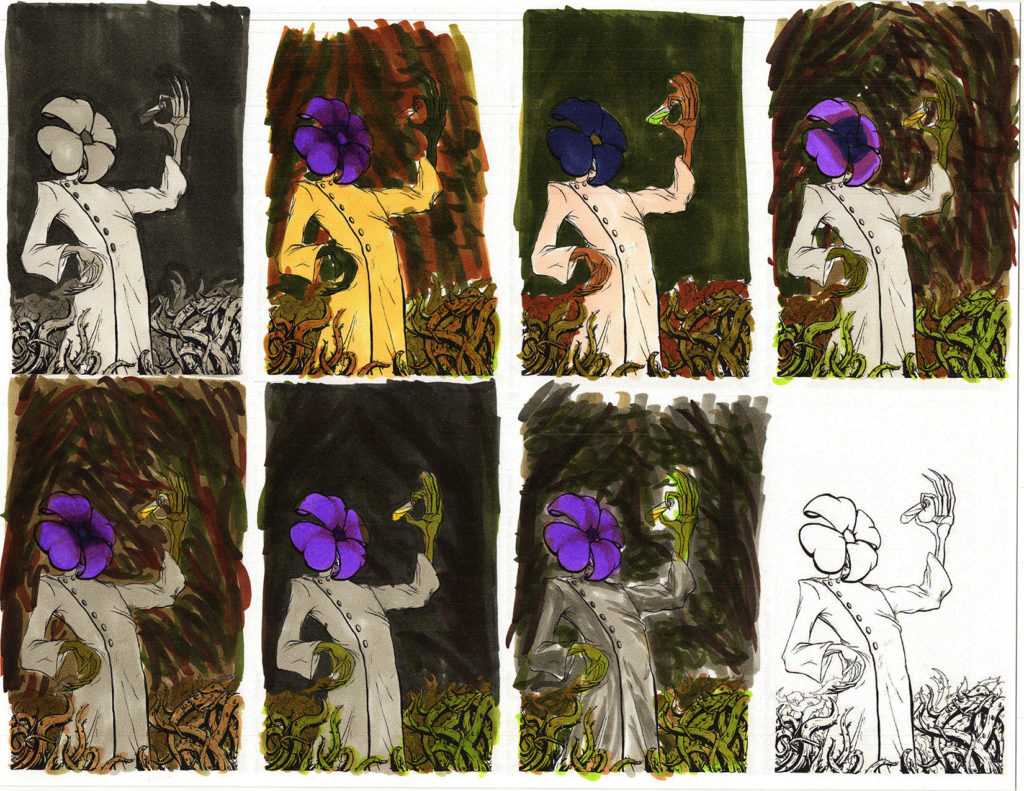

I tried thumbnails; hoping they would help me figure something out.

They did not help and the panic began to cement.

However, I knew the basic colours I wanted to use. So, I figured that I’d just start with those and hope for the best!

I did what are known as “flats”: roughed-in base colours with no shading or hue variation.

I liked how the colours worked together but the piece was boring. It had no emotion. It had no drama. It was, well… flat.

At the time I couldn’t articulate what was wrong. I just knew that it was wrong and that I didn’t know how to fix it.

That Time I Quit Art

Despite only spending a few minutes working on the flats that day, I decided to stop working on it and only come back once I had some time to think about what to do next.

The next day, I had no new insights and I hated the piece.

The day after, I was still insightless and I hated it even more.

By the next week, I was so unhappy looking at the drawing on my desk, that I packed up and hid it.

For the next month, thinking about it would keep me up at night.

Finally, I came to the conclusion that I was a talentless hack. I had no future with art.

I decided that I was never going to make another piece of art again.

I gave up. I felt better. I could sleep at night. Life was good… for about a week.

Then, I started worrying about what to do with my life if art wasn’t in it.

I would manage to calm down and move on but every now and again, the existential dread would slip in.

The cycle repeated; on and on.

As it progressed, it became easier and easier to convince myself that I could live without making art. And, eventually, I was done. I had quit art for good.

Eureka!

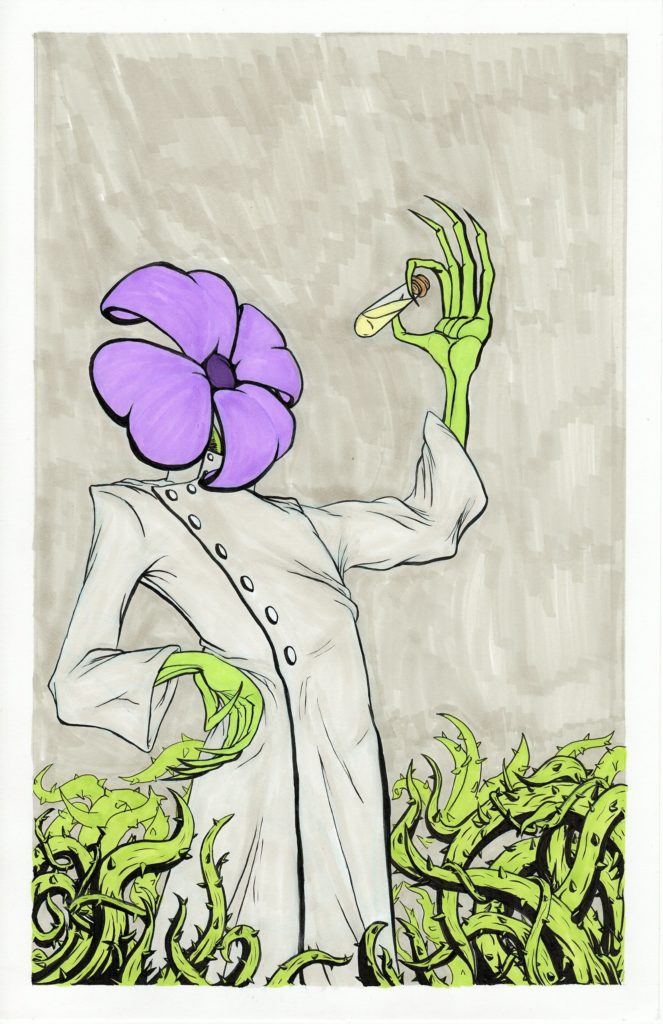

I had officially quit art for three months when, suddenly, I woke up from a deep sleep at 2am. The tension drained away and everything was good in the world. I knew what I had to do. I knew how to fix the Professor. I could go back to sleep, and in the morning I’d be an artist again!

The problem was, I was too excited. I lay in bed until 3am but found that I couldn’t go to back to sleep.

I guess I couldn’t wait until morning. I was an artist now. So, I jumped out of bed, cleared my workspace, dug out the drawing, and got down to business.

My grand idea was to use the “serum” as a secondary lightsource. It added all the mood and interest that was lacking in the flats.

I started colouring at 4am and finished the piece eight hours later.

I’m proud of the work done and the lessons learned.

Conclusion

If you’re having trouble with something, sometimes working on something else is the best way to solve your problem. It turns out that, if something is important to you, your subconscious will keep working on it even if your conscious mind has moved onto something else.

This has happened to me many times since then, and in retrospect, many times before; I just hadn’t realized it. Usually, it doesn’t take three months. But, if that’s what it takes, that’s what it’s going to take.

I hope you found this to be an interesting peak at my process and, I guess, psyche.